Style guide: Social Security Tribunal of Canada decisions

Part 1 – Writing strategies

By adopting the following strategies, you will be able to write legally sound, plain language decisions.

Clarity is the main goal. Right at the beginning, tell your readers what you have decided. This will help them follow you as you explain your reasoning behind your decision because they will already know what to expect. Along the way, you can pause to explain any unfamiliar legal wording or concepts.

Here are tried-and-tested strategies for writing plain language decisions.

Start with a solid structure

A solid structure will serve as the backbone for your decision. Organizing your ideas well will communicate them clearly.

The most recent decision templates in Atrium give you solid examples for how to structure your decision.

Follow the point-first approach at every level

Give the most important information first, not only at the document level (the decision as a whole), but also at the paragraph and sentence level. This is called the point-first approach.

You should be able to follow the progression of the decision by reading only the topic sentences (first sentences) of each paragraph. When read in order, the topic sentences should give a summary of the decision. So, stick to one main idea per paragraph. There is no harm in having short paragraphs of simply one sentence or a few sentences.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| [20] The Claimant was present at a career fair. He submitted eight employment applications to prospective employers. He was invited to three interviews and attended each of them. Therefore, I find that the Claimant made enough efforts to find a suitable job. | [20] The Claimant made enough efforts to find a suitable job. He attended a job fair. He applied for eight jobs. He also had three interviews. |

Draw attention to important information

Long, dense paragraphs can be daunting. Information should be easy to find. One way to draw attention to information is to create white space. There are a few ways to do this.

Use headings

Use headings as signposts.

Headings tell your readers what is next. They should be short and easy to understand. Try to keep them to one line.

Headings should never contain findings that aren’t fleshed out in the paragraphs.

Main headings give your readers the general layout of the decision. Different divisions may use different headings. Here are some examples:

| Main heading | What it introduces |

|---|---|

| Decision | What is the outcome? This section states upfront what you have decided. |

| Overview | What is the background? This section anchors the reader in the context without overwhelming them with too much detail. |

| Issues | What are the issues you have to address? |

| Analysis | What is your thought process behind the decision? |

| Conclusion | So, what is the outcome of all this again? |

Subheadings and sub-subheadings should be contextually relevant. Adapt them to each decision and the readers’ needs.

Use lists

You can use a list if you need to mention at least three related items or pieces of information. The white space and bullets or numbering will direct your readers to each point.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| The Claimant has to prove that he had the desire to return to the labour market as soon as a suitable job was offered, that he made efforts to find a suitable job, and that he did not set personal conditions that might have unduly limited his chances of returning to the labour market. |

The Claimant has to prove three things:

|

A list can be especially helpful when reporting a series of events or presenting the points from someone’s testimony or arguments. A list can also help you avoid repeating speech verbs.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| In her arguments, the Applicant pointed out that she is elderly, so the appeal situation is unfair. She said that relevant documents have been lost or destroyed. She stressed that her memories have faded. In addition, she shared that she has ongoing medical conditions. She emphasized that the stressful appeal situation is making her medical conditions worse. |

The Applicant argued that the appeal situation is unfair because:

|

See Lists for a description of how to make lists.

Use bold font

Use bold font (not italics) to draw your readers’ attention to a word or phrase.

This is especially helpful when highlighting a key word you want to explain and when drawing your readers’ attention to a contrast.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| [8] Income includes any income that a claimant did or will get from an employer or any other person, whether it is in the form of money or something else. Employment includes any employment under any kind of contract of service or employment. |

[8] Income can be anything that you got or will get from an employer or any other person. It doesn’t have to be money, but it often is. [9] Employment is any work that you did or will do under any kind of service or work agreement. |

Write how you speak

Write as if you were speaking, but adapt your writing to your readers’ needs.

Contractions

You may use contractions that people use when they speak (example: can’t, I’m, there’s). However, use good judgement in deciding whether contractions will help your readers. Contractions could confuse your readers if they have low literacy skills.

We recommend using contractions for common negated auxiliaries. These types of contractions can prevent misunderstandings. For example, readers could easily skip over the “not” in “is not” and read it as an affirmative. This doesn’t happen when the negation and the verb are expressed as one word, such as “isn’t."

The Supreme Court of Canada uses contractions for common negated auxiliaries in its Cases in Brief.

Use:

- isn’t (is not) / wasn’t (was not)

- aren’t (are not) / weren’t (were not)

- can’t (cannot) / won’t (will not)

- don’t (do not) / didn’t (did not)

- hasn’t (has not) / haven’t (have not)

Avoid complex contractions because they can be harder for people with low literacy skills to understand.

Don’t use:

- shouldn’t (should not)

- should’ve (should have)

- couldn’t (could not)

- could’ve (could have)

- wouldn’t (would not)

- would’ve (would have)

- mustn’t (must not)

Note: Don’t use a contracted negated auxiliary when contrasting elements and emphasizing the negation.

Example:

The Tribunal can interpret the law, but it cannot change it.

Transitions

You can use transitional markers to create flow and cohesion between sentences and ideas.

Use transitions to:

- clarify (example: for example, in other words, that is)

- conclude or summarize (example: so, this means)

- compare and contrast (example: but, likewise, on the other hand)

- show consequence (example: because of this, for this reason, as a result)

- give further details (example: also, and, besides)

- emphasize a point (example: in fact, again, above all)

- show sequence (example: first, second, finally, afterward, meanwhile)

Use short sentences

Express only one idea in each sentence. Instead of trying to convey a complex idea in a single sentence, break it up into smaller parts and make each one the subject of its own sentence.

Keep the subject, verb, and object close together. The natural word order of an English sentence is subject-verb-object (example: The Appellant appealed the decision).

When you put modifiers, phrases, or clauses between these essential parts, you make it harder for readers to understand you.

When introducing a condition, it is best to start the sentence with “if” (or any other limiting conjunction). This helps the reader understand the relationship between the clauses.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| A claimant is not automatically entitled to EI benefits if he or she voluntarily left an employment. | If a claimant voluntarily quits a job, they aren’t automatically entitled to EI benefits. |

Use the active voice

Using the active voice means that the subject of the sentence comes first and performs the action that the rest of the sentence describes.

The active voice is the most straightforward way to present your ideas because it creates a clear image in the reader’s mind of who is doing what.

In the passive voice, the target of the action gets promoted to the subject position.

Example:

| Don’t write (passive) | Do write (active) |

|---|---|

| It was decided by the committee that the Claimant would not return to his position. | The committee decided that the Claimant would not go back to his position. |

The passive voice may be a good choice only when:

- we don’t know who did what

- who did it isn’t relevant

- we want to emphasize what was done rather than who did it (example: The Claimant was hit by a car.)

Use common words

Whenever possible, choose words that are likely to be more familiar to the reader. You are the expert of your case, and you know best what your parties will easily understand.

Generally, avoid:

- Latin-based words when appropriate

- Instead, use Anglo-Saxon terms and expressions when possible.

- abstract language

- This includes idioms and cultural references (example: dead tired, ball in their court).

- legal wording

- complex medical terminology

Here are some examples:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| i.e. | that is |

| e.g. | for example |

| de novo hearing | new hearing |

| employment | job |

| lumbar pain | lower back pain |

| cerebrovascular accident | stroke |

| oncological treatment | cancer treatment |

| prior to | before |

| to obtain | to get |

| to attempt to / to endeavour to | to try to |

| to require | to need / to want / to call for |

| to provide / to issue | to give |

| to turn on | to depend on |

| to demonstrate | to show |

| to err | to make an error |

| to proceed | to go to the next step / to go ahead |

Explain legal wording

Sometimes, it isn’t possible to avoid legal wording. If you use legal wording without explaining it, your readers may not understand your decision.

Here are some strategies:

Paraphrase

Introduce the legal wording; then explain it in different terms in the following sentence or sentences. You can use transitional markers to tell your readers that you are rephrasing the legal wording for clarity.

For example, use:

- This means

- In other words

- So

- That is

Since the legal wording is left intact, you may not have to add a footnote.

Although this strategy could lengthen your decision, clarity is the focus in plain language writing.

Example:

The law says I have to look at whether her efforts were sustained and whether they were directed toward finding a suitable job. In other words, the Claimant has to have kept trying to find a suitable job.

If the legal wording is more complex, explain or substitute it by using more accessible wording. Then, use a footnote to make a clear link between the accessible wording and the established legal wording. In the footnote, explain the legal wording and reference the relevant legislation or case law.

Example:

This means that the Claimant’s application can’t be treated as though it was made earlier.1

[…]

1 Section 10(4) of the Employment Insurance Act (EI Act) uses the term “initial claim” when talking about an application.

This strategy is similar to the early English legal practice of using legal doublets to address audiences with different linguistic and legal backgrounds (example: will and testament, bind and obligate). In a sense, you are drawing from tradition by applying an old technique to a modern context to help make justice accessible.

Parentheses

In parentheses, give a plain language synonym for the legal wording. This works best when you need to clarify a single legal term.

Example:

For the Applicant’s file to go to the next step, she needs leave (or, permission) to appeal.

Note: If you are unsure how to explain legal wording in plain language, talk to your vice-chairperson or to Legal Services.

Avoid unnecessary words

Keep your text light and easy to read by avoiding unnecessary words. You can do this by:

- simplifying prepositional phrases into single words

- cutting excess modifiers

- omitting redundant words

Here are some examples:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| in order to / for the purpose of | to |

| on the basis of | on / based on |

| whether or not | whether |

| to summarize briefly | to summarize |

| in respect of | regarding / for |

| in relation to / with regard to / with respect to | about / on / regarding / concerning |

| as a result of / for the reason that | because |

| owing to the fact that / arising from the fact that / in view of the fact that | because / since |

| in consideration of | considering / based on |

| during the course of / for the duration of | during |

| in the absence of | without |

| in the near future | soon / shortly |

| in the event that | if |

| until such time as | until |

| a past history of | a history of |

Avoid nominalization

Readers will understand your message more clearly when you choose verbs over verb-noun phrases.

Here are some examples. We have also included a plain language alternative when possible:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| to come to the conclusion | to conclude / to find |

| to conduct a review | to review |

| to carry out an examination of | to examine / to look at |

| to make an attempt | to attempt / to try |

| to make arrangements | to arrange |

| to give consideration to | to consider |

| to make reference to / to make a reference to | to refer to |

| to submit an application / to file an application | to apply |

| to file an appeal with | to appeal to |

Avoid excessive negation

Writing in the negative creates another obstacle to understanding the text. It is important to present information using positive terms when possible; using the affirmative can help with this.

Example:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| You can’t appeal to the Tribunal if the Minister hasn’t first issued a reconsideration decision. | The Minister has to issue a reconsideration decision before you can appeal to the Tribunal. |

When a sentence contains two negations, they cancel each other out (example: not unavailable for work). This could result in a meaning that is the opposite of what you intended.

At times, there isn’t a way around using two negations (example: “not disentitled” doesn’t necessarily mean “entitled” in the Employment Insurance context). However, you should avoid or explain these whenever possible.

Many ordinary words have a negative meaning (example: unless, fail to, except, excluding, other than, terminate, void, insufficient, unemployed). Watch out for them when they appear after “not.”

Part 2 – Inclusive writing

Gender-inclusive writing

Gender-inclusive writing means avoiding references to gender whenever possible. It is a standard across government.

The golden rule is to address people the way they have asked to be addressed.

Avoid courtesy titles

Drop gendered courtesy titles (example: Ms., Mrs., Mr.). Instead, refer to individuals by their first and last name once in the beginning of the decision to establish who the parties are. Then, refer to them by their role in the case in the rest of the decision.

Example:

Jane Doe is the Applicant in this case. She applied for disability benefits in November 2018.

[…]

The Applicant appealed the Minister’s decision to the Tribunal’s General Division.

Use gender-inclusive pronouns

Generic “you”

Use the generic “you” and its other grammatical forms (example: your, yours) to refer to an unspecified person. It replaces “one” in formal writing.

The generic “you” can be helpful because it contextualizes what you are writing. It communicates that what you are saying applies generally to anyone; that includes the claimant or applicant in the benefits situation. It can give your decision a relaxed tone.

Example:

The law explains what it means by “just cause.” The law says that you have just cause to leave your job if you had no reasonable alternative to quitting when you did.

Note: Avoid the specific “you” for one party because there is more than one party in an appeal.

Singular “they”

Use the gender-neutral singular pronoun “they” and its other grammatical forms (example: their, theirs, them) when the gender of the antecedent (the word the pronoun refers to) is unknown or irrelevant.

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

| Case law lists three factors a claimant has to prove to show that he or she is “available” in this sense. | Case law gives three things a claimant has to prove to show that they are “available” in this sense. |

Note: When referring to entities or organizations (example: the employer, the Minister), use “it.”

Use the gender-neutral singular pronoun “they” when an individual is non-binary (that is, they don’t identify with the masculine or feminine gender), unless they have identified a different pronoun.

Example:

The Claimant in this case is Anna Smith. They applied for disability benefits on August 13, 2020.

There are other gender-neutral singular pronouns to refer to a non-binary person (example: “zie”). But “they” is by far the most common. It has been in constant use in English writing since the 1300s.

Note: If someone identifies as non-binary, ask how they would like to be addressed, if that isn’t clear from their file.

Use gender-inclusive nouns

Instead of referring to gender-specific titles or roles, use a gender-neutral equivalent.

Here are some examples:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| husband / wife | spouse / partner |

| handyman | maintenance worker |

| housewife | homemaker |

| landlady | property owner |

| policeman | police officer |

| foreman | supervisor |

| cleaning lady | janitor |

| fisherman | fisher / fish harvester |

See the Translation Bureau’s gender-inclusive writing recommendations for more in-depth guidelines and examples.

Writing about disabilities

Use person-first constructions that put the person ahead of the disability. In other words, don’t define the person by their illness, disability, or experience.

For example, instead of “a diabetic” or “a wheelchair-bound person,” use “a person with diabetes” or “a person who uses a wheelchair.”

Avoid using language that casts disabilities as negative. For example, avoid using phrases such as “suffers from,” “afflicted with,” or “victim of,” since such expressions cast disabilities as negative attributes.

Here are more examples:

| Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|

| disabled person | person with a disability / person with disabilities |

| handicap | disability / impairment |

| developmentally disabled person | person with an intellectual disability |

| blind person / person who has sight loss / visually impaired | person who is blind / person with a visual impairment |

| deaf person / hearing impaired person | person who is deaf / person who is hard of hearing |

| mentally ill person | person with a mental health disability |

Some expressions, like “person with a mental health disability,” are broad. If relevant, you can specify the disability (example: “the Applicant has schizophrenia”). However, note that some words like “disability” may have certain legal connotations.

See ESDC’s suggestions for portraying people with disabilities for more in-depth guidelines and examples.

Part 3 – Writing conventions

Punctuation

Oxford comma

Use the Oxford comma. It is the comma before “and” at the end of a list within a sentence.

Example:

The General Division made an error of law by interpreting the law without fully considering its text, context, and purpose.

Ellipses

Use ellipses (three dots … ) to indicate that you have omitted text from a quote.

- Do: Put the ellipsis in square brackets if the omitted text is in the middle of the quote, or if you are omitting an entire paragraph.

- Don’t: Use square brackets if the omitted text is at the end of the quote; instead, add an extra dot to signify a period, when required.

- Don’t: Use ellipses at the beginning of a quote, even if the quote begins mid-sentence.

Example:

In her report, Dr. Riviera states that the Claimant has a long history of “chronic pain and insomnia […] unimproved by medication ….”

Capitalization

Parties

For parties:

- Do: Capitalize the first letter when you are referring specifically to the individual claimant, applicant, appellant, respondent, or added party. Consider it a substitute for their name.

- Do: Capitalize a specific employer at the beginning when they are a party.

- Don’t: Capitalize the first letter when you are referring to claimants, appellants, employers, etc. from other cases or in the generic sense.

Examples:

| Capitalize | Don’t capitalize |

|---|---|

|

The Claimant said that he tried to go back to work. |

First, a claimant has to ask the Commission to reconsider its decision about getting benefits. |

|

Business Inc. is the Added Party (Employer). The Employer stated …. |

The Claimant worked for her previous employer for three months. |

Organizations

For organizations:

- Do: Capitalize the title of all official names of organizations, levels of government, departments, and agencies.

- Do: Capitalize short forms of the full title of government bodies when they stand for the full title.

- Don’t: Capitalize generic names of organizations.

Examples:

| Capitalize | Don’t capitalize |

|---|---|

|

He had worked for the Toronto District School Board since 2010. |

He had worked for the school board since 2010. |

|

The Claimant appealed the Minister’s reconsideration decision to the Tribunal’s General Division. |

You can appeal a decision from a federal tribunal to a federal court. |

|

The Government of Canada provides EI services through Service Canada. |

The Canadian government issued the Claimant a new passport. |

Official documents

For official documents:

- Do: Capitalize the names of official documents and forms when referring specifically to the document itself.

- Don’t: Capitalize the shortened or generic names of official documents.

Example:

| Capitalize | Don’t capitalize |

|---|---|

|

The Arthritis Programs and Services Report indicates that the Appellant has had knee problems for four years. |

The arthritis program report indicates that the Appellant has had knee problems for four years. |

Medication

For medication:

- Do: Capitalize the first letter of brand name medication (example: Advil).

- Don’t: Capitalize the first letter of generic medication (example: ibuprofen).

Abbreviations

Avoid abbreviations if possible. It can be difficult for readers to keep track of what a technical abbreviation means.

If your decision mentions only one piece of legislation, consider writing “the law” and explaining in a footnote that you are referring to the Canada Pension Plan, for example.

If you can’t avoid abbreviations, give the term in full the first time you use it and include the abbreviation in parentheses immediately after. There is no need for quotation marks or other words in the parentheses.

Example:

Department of Employment and Social Development Act (DESD Act)

If your decision mentions a few different laws, you may be able to give them one-word shortened forms that don’t include initials.

Example:

The Employment Insurance Act (Act) and the Employment Insurance Regulations (Regulations) explain the rules a claimant has to follow.

If you have to choose a more precise abbreviation to distinguish laws, choose a well-established abbreviation that gives more information for a non-legal audience. In the following examples, readers will at least know from the abbreviation that you are referring to legislation. That isn’t clear from “EIA,” “EIR,” and “DESDA.”

Examples:

| For | Don’t write | Do write |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Insurance Act | EIA | EI Act |

| Employment Insurance Regulations | EIR | EI Regulations |

| Department of Employment and Social Development Act | DESDA | DESD Act |

Once you note the abbreviation, refer only to the abbreviation in the rest of the document; don’t revert to writing the full term. However, treat footnotes differently. People don’t always read footnotes as they read the paragraph text. So for accessibility, it can be helpful to establish the abbreviation in the footnote too.

Don’t give a term an abbreviation if the term appears only once in the document.

Italics

If possible, avoid italics because they can be difficult to read.

Do italicize:

- styles of cause (example: Villani v Canada (Attorney General), 2001 FCA 248)

- the shortened names of cases (example: Villani)

- full names of statutes and regulations (example: Department of Employment and Social Development Act, Employment Insurance Act, Canada Pension Plan, Social Security Tribunal Regulations)

- foreign words that have not been anglicized (example: sic, res judicata)

Don’t italicize:

- the abbreviated names of statutes and regulations (example: the Act, the CPP)

- the names of programs (example: Canada Pension Plan disability benefits, Employment Insurance benefits)

- for emphasis; use bold instead

Verb tenses

Present tense

Use the present tense when referring to opinions, thoughts, feelings, etc. that are still current. This includes instances when parties state their arguments.

Examples:

- The Appellant believes that the General Division made an error.

- The Minister argues that the General Division didn’t make an error.

Use the present tense for the Tribunal’s analysis and conclusion.

Example:

- The Tribunal finds, concludes, notes, determines, etc.

Past tense

Use the past tense when referring to written submissions and when there is a time marker.

Examples:

- In her application, the Applicant failed to say why she wanted to appeal.

- In its written response, the Commission argued that the Claimant wasn’t entitled to benefits.

Use the past tense for testimony and submissions given during the hearing.

Example:

- At the hearing, the Respondent explained that there was no basis for this argument.

Past perfect

Use the past perfect to indicate that an action was completed before another event in the past. It is important to use this tense to create a logical timeline when describing events.

Example:

- When the Appellant called his doctor, he had been sick for a week.

Spelling

Make sure to set your default language to English (Canada).

- Click on the language icon “Language” icon in Microsoft Word in the Review tab and select “Set Proofing Language….”

In addition to Word’s spellcheck, you can check your spelling using Antidote.

Numbers

Spell out one-digit numbers and use numerals for the rest (example: 10 and above).

Examples:

- The file contained nine medical reports.

- The file contained 20 medical reports.

But, for consistency, one-digit numbers should be expressed as numerals if other numbers in a given sentence or passage are numerals.

Example:

- Out of the Claimant’s 16 jobs, 11 were manual labour, 2 were childcare, and 3 were administrative.

When a sentence begins with a number, always spell it out or rearrange the sentence.

Avoid ordinals when possible (example: write “tenth anniversary” not “10th anniversary”). If you must use an ordinal, don’t superscript it.

Dates

Use only cardinal numbers in dates (example: write “April 8, 2020,” not “April 8th, 2020”).

Use a comma before and after the year when citing a date in full, even if the date is used as an adjective (example: The April 8, 2020, report by Dr. Turner).

Lists

Lists give the information your readers need in an easy-to-follow way. A long paragraph can be overwhelming. If you need to mention at least three related items or pieces of information, use a list.

Use lists to express points that are more easily grasped separately than together.

Put a colon (“:”) at the end of the lead-in sentence or phrase. It tells your readers that a list is coming. Try to keep the lead-in sentence and the listed items on the same page.

If you need to make it clear that your list is inclusive, use wording such as “the following” in the lead-in sentence.

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

|

Regarding her efforts, the Appellant says that she:

|

The Appellant says that she made the following efforts:

|

Note: Bullets should align with the text above. The indentation is normally 1.27 cm for first-level bullets and 1.9 cm for second-level bullets.

If you need to make it clear that your list is exclusive, use wording such as “at least one of the following factors.”

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

|

I have to determine whether the General Division:

|

I have to determine whether the General Division made at least one of the following errors:

|

Give the items in a list so that they are parallel (example: all begin with a noun or verb, all are questions, etc.).

Capitalize items in a list only when the lead-in and all the items are independent clauses, meaning they can stand alone as sentences, as in the example in the “Do write” column above. End the items with the appropriate punctuation mark.

Use bulleted lists “Bullets” icon in Microsoft Word for items that don’t have to be in a specific order.

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

| The Claimant has a number of functional limitations. Specifically, he has lower back pain and severe pain in his left ankle and foot. He is also unable to walk or stand for long periods. |

The Claimant explains that his functional limitations are the following:

|

Use numbered lists “Numbering” icon in Microsoft Word for items that have to be in a specific order, such as a timeline of events. Generally, we recommend using lower-case letters in numbered lists so readers don’t confuse a list number with a paragraph number.

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

|

[20] The Appellant described the circumstances of his dismissal as follows:

|

[20] The Appellant described the circumstances of his dismissal as follows:

|

Spaces

An easy way to spot spacing issues is to select the “Show paragraph marks and other hidden formatting symbols” option at Paragraph under the Home tab.

Make sure the spacing is consistent throughout the document.

Add only one space between the period and the first word of the next sentence.

Non-breaking space

A non-breaking space is the same width as a word space, but it prevents the text from flowing to a new line or page. Use non-breaking spaces (Ctrl + Shift + Space) to avoid an awkward break. With the “Show paragraph marks and other hidden formatting symbols” option selected, a non-breaking space looks like the degree symbol (“ ° ”).

Use a non-breaking space:

- between a numeral and its unit (example: 45°kg, 6°p.m.)

- between a title and a name (example: Dr.°Singh)

- between the month and the day (example: February°15, 2020)

- after reference marks (example: section°2, para°45, paras°4 and 5)

This style guide also describes how to use the non-breaking hyphen.

Part 4 – References

Footnotes

Readers should not have to read footnotes to understand a decision. Instead, you should use footnotes to help with the overall readability of your decision.

See Explain legal wording for tips on how to make legal wording more accessible by using footnotes.

When to use footnotes

Use footnotes for citing:

- evidence

- statutes and regulations

- case law

Using footnotes will:

- help you keep short, clear sentences by not interrupting a passage with lengthy reference information

- give you a place to provide your legal references for the interested legal audience without distracting your other readers

- give you a place to explain your plain language paraphrasing of technical wording to the interested legal audience by pointing them to the relevant legislation or case law

Footnote conventions

Footnotes follow these conventions:

- Place the footnote superscript number at the end of a sentence in the paragraph text, following all punctuation marks.

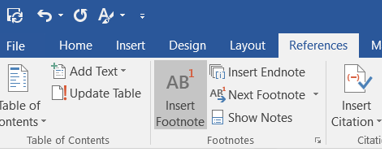

- Under the References tab, click on “Insert Footnote.”

- Use a maximum of one footnote per sentence. If you need to make a few references in one sentence, consider breaking the sentence into a few sentences or including the references in a single footnote.

- Use full sentences in the footnote. Give directions or be descriptive.

- Avoid Latin abbreviations like Ibid. and supra. Some readers might not know what these mean. Instead, repeat the footnote details.

Footnote formatting

- Arial, 10-point font

- footnote superscript followed by a single space, then footnote text

- first letter capitalized

- 1.0-line spacing with 0 point before and 0 point after

- left justified (click on the “Align Left” icon in Microsoft Word icon)

- period at end

- case law decisions separated with a semi-colon (if referring to more than one in a single footnote)

Examples:

3 See Canada (Attorney General) v Somwaru, 2010 FCA 336; and Canada (Attorney General) v Kaler, 2011 FCA 266.

4 Section 10(4) of the Employment Insurance Act (EI Act) uses the term “initial claim” when talking about an application.

5 Section 12 of the Social Security Tribunal Regulations sets out this rule.

Citing evidence

Appeal record

When you cite evidence from the appeal record, give directions or be descriptive; don’t simply mention the page number, such as “GD3-14.”

Examples:

- See GD3-6.

- See the evidence at GD3-6 in the appeal record.

- See the report at AD3-11 to AD3-14 in the appeal record.

- This point is mentioned at GD2-30 in the appeal record.

Recordings

Use the following format when you give a timestamp for a hearing recording: h:mm:ss.

Examples:

- This is from the audio recording of the November 14, 2020, hearing at 1:30:05 to 1:32:25.

- This is what I heard from the audio recording of the General Division hearing at approximately 0:25:40.

Citing statutes and regulations

References to statutes and regulations have to be clear to all the parties, even those who are unfamiliar with law.

Follow these guidelines:

- Start with “See” or other directional or descriptive wording.

- Write out “section” (or “sections”) no matter what level of reference it is: section, subsection, paragraph, and subparagraph.

- Give the full name of the statute or regulation in italics the first time you use it in a footnote.

- Add an abbreviation if it will appear again. Then, use the abbreviation in the relevant footnotes that follow.

Examples:

- See section 30(1) of the Employment Insurance Regulations (Regulations).

- This is based on sections 19 and 44(2.1) of the Canada Pension Plan.

- Section 69 of the Canada Pension Plan sets out this rule.

Citing case law

References to case law also have to be clear to all the parties.

Follow these guidelines:

- Start with “See” or other directional or descriptive wording.

- Give the full name of the style of cause in italics.

- Don’t put a period immediately after the “v” between the parties’ names.

- If you need to mention the case in the paragraph text, write the shortened form (example: “in a case called Hastings”). Give the full form in the footnote.

- Include the neutral citation, if one is available.

Examples:

- See Ferreira v Canada (Attorney General), 2013 FCA 81.

- The Federal Court of Appeal explains this decision-making approach in Klabouch v Canada (Attorney General), 2008 FCA 33.

- See Canada (Attorney General) v Falardeau, A-396-85; and Lemay v Canada Employment Insurance Commission, A-662-97.

- See Faucher v Canada Employment and Immigration Commission, A-56-96 and A-57-96.

Part 5 – Formatting

Decision templates

The SST uses formatting that helps with readability. Before you start writing your decision, make sure you use the most recent decision template. Use the templates in Atrium so that your decisions are consistent with other SST decisions in how they look and read.

Using Atrium decision templates has benefits:

- They have the right formatting built in.

- They often set out the legal tests.

- Some are already in plain language.

Avoid using an old decision as a template.

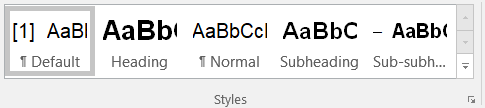

Word “Styles”

Templates have Microsoft Word “Styles” (not macros) built in for your different formatting needs. You should be able to click on the Style you want. The Styles bar is under the Home tab. It usually looks like this:

The sections below describe the formatting features of a decision template. We will point to Styles where they are available in templates.

Margins

- Title page: Narrow – 1.27 cm

- Body of text: Normal – 2.54 cm

Page numbering

- centred at top of page, with no hyphens or special symbols (example, simply: 2)

- no page number on cover page

- decision starting on page 2

Font type and size for paragraph text

- Arial, 12-point font

Line spacing

- 12-point spacing after each paragraph

- 1.5-line spacing within and between paragraphs

Click on the “Line and Paragraph Spacing” icon in Microsoft Word icon or the corner arrow in Showing where to find the “Paragraph Settings” icon in the Microsoft Word menu for line spacing options.

Main headings

Use the built-in headings in the decision templates. The Style is called “Heading.”

|

Example: Decision |

Formatting specifications:

- Arial, 16-point font

- bold

- 1.0-line spacing with 0 point before and 12 point after

- only first letter of first word capitalized

- not underlined (underlining for hyperlinks only)

- not numbered (numbers only for paragraphs)

- keep-text-together options selected

Subheadings

Use the built-in subheadings in the decision templates. The Style is called “Subheading.”

|

Example: Capable of and available for work |

Formatting specifications:

- Arial, 14-point font

- bold

- 1.0-line spacing with 0 point before and 12 point after

- only first letter of first word capitalized

- not underlined (underlining for hyperlinks only)

- not numbered (numbers only for paragraphs)

- keep-text-together options selected

Sub-subheadings

Use the built-in sub-subheadings in the decision templates. The Style is called “Sub-subheading.”

|

Example: – Wanting to go back to work |

Formatting specifications:

- non-bold en dash (“–”) at beginning (hold down Ctrl and type “-” key on number pad or hold down Alt and type “0150” on number pad)

- Arial, 12-point font

- bold text

- 1.0-line spacing with 0 point before and 12 point after

- only first letter of first word capitalized

- not underlined (underlining for hyperlinks only)

- not numbered (numbers only for paragraphs)

- keep-text-together options selected

Paragraphs

You must write within numbered paragraphs.

Use the built-in paragraph format in the decision template. The Style is called “Default.”

|

Example: [1] I am allowing the appeal. |

Formatting specifications:

- Arial, 12-point font

- 1.5-line spacing with 0 point before and 12 point after

- left justified (click on the “Align Left” icon in Microsoft Word icon)

- paragraphs numbered sequentially in square brackets, starting from 1

- paragraph numbers aligned with headings

Footnotes

- Arial, 10-point font

- 1.0-line spacing with 0 point before and 0 point after

- left justified (click on the “Align Left” icon in Microsoft Word icon)

- not indented

Quotations

Short quotes (fewer than five lines)

Embed the quote directly into the paragraph.

Example:

The Claimant didn’t agree with the employer that she was “not a good fit.”

If “that” comes before a quote within a sentence, don’t capitalize the first word of the quote (unless it is part of a proper noun). Also, the first letter of the word should be in square brackets if it is written differently than in the original text.

Example:

He wrote that “[t]he patient has anxiety issues that keep her from working.”

Place punctuation inside the quotation marks.

Example:

To have “just cause,” you have to prove that you had no reasonable alternative to leaving.

Long quotes (five lines or longer)

Try to avoid long quotes. There is usually no need to copy and paste legislation or case law word for word because you will need to explain the technical wording anyway. Try paraphrasing the quoted text in plain language and referencing the source material in a footnote. See Explain legal wording for strategies.

Example:

| Don't write | Do write |

|---|---|

|

The Regulations require me to consider whether the Claimant’s efforts were reasonable and customary. Section 9.001 of the Regulations reads:

|

The law sets out criteria for me to consider when deciding whether the Claimant’s efforts were reasonable and customary.3 I have to look at whether her efforts were sustained and whether they were directed toward finding a suitable job. In other words, the Claimant has to have kept trying to find a suitable job. […] 3 See section 9.001 of the Employment Insurance Regulations. |

However, if a long quote is unavoidable:

- set the quote apart from the rest of the paragraph

- use 1.0-line spacing “Line and Paragraph Spacing” icon in Microsoft Word

- 12-point spacing after the quoted text

- indent the quote 2 cm on each side

- left justify the quote “Align Left” icon in Microsoft Word

- put the first letter of the first word in square brackets if it is written differently than in the original text

Example:

[20] According to the Commission agent, the Appellant gave the following answer:

I had started to look before quitting. I hadn’t secured a job. I thought I would have a better chance if I quit and dedicated myself full-time to find full-time work. I had no real prospects or offers at the time I quit. In fact, I wasn't having any luck.

Finally, the job at Business Inc. came up. I was told it would only be temporary and I would be filling the position of someone on leave. But, I had been without work and without prospects for a while, so I took that job.3

3 See Supplementary Record of Claim dated October 3, 2019, at GD3-30.

Keeping text together

Sometimes a heading, sentence, or word appears on its own at the end of a page or on a new page. (If you are using the templates, the different levels of headings will have the keep-text-together setting built in.)

To keep text together:

- select the dangling heading or text

- right-click and select “Paragraph…” or click on the corner arrow in Showing where to find the “Paragraph Settings” icon in the Microsoft Word menu

- go to the “Line and Page Breaks” tab

- select

- “Widow/Orphan control,” “Keep with next,” and “Keep lines together” for headings, lead-in sentences for lists, and the last paragraph of the decision*

- “Widow/Orphan control” and “Keep lines together” for sentences and words

* This keeps the last paragraph with the member’s signature and division information.

Non-breaking hyphen

A non-breaking hyphen (Ctrl + Shift + Hyphen) is called the “hard hyphen.” It keeps a hyphenated word together as a whole on the same line. Use it when a hyphenated word (example: re-read) or file name (GD-XX-XX) gets broken at the end of a line.

This style guide also describes how to use the non-breaking space.

Part 6 – Checklist for decisions

Proofreading

Always re-read your decision to:

- catch mistakes

- make sure you haven’t forgotten anything

- check that your ideas are clear and organized well

- After you finish your first draft, wait at least a few hours before you proofread your decision. This helps you look at your decision with fresh eyes.

Final check

| To check | |

|---|---|

| Template used is the most recent; font and formatting are correct | |

| File number and names of parties are correct; preferred pronouns used | |

| Point-first approach followed at every level; topic sentences give a summary | |

| Short sentences and short paragraphs used | |

| Long sentences broken down; lists used where possible | |

| Common words used; legal wording explained | |

| Double negatives rephrased | |

| Footnotes used when referring to the appeal record, statutes and regulations, and case law | |

| Dates, amounts of money, and other numbers are correct | |

| Abbreviations avoided or used consistently | |

Part 7 – Additional resources

For a more in-depth review of the topics covered in this guide, we recommend you consult the following reference tools. Note that some tools address writing for certain contexts that may not apply to your situation.

Terminology and writing guidelines

Canada.ca Content Style Guide (focus on web-publishing)

Suggestions for the portrayal of people with disabilities – General guidelines (ESDC)

Referencing guidelines

Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (“McGill Guide”) – latest edition (no online version available)

Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (“McGill Guide”) Queen’s University summary

Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (“McGill Guide”) University of Alberta summary

Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (“McGill Guide”) Carleton University summary